Versión en castellano (english version below)

Gracias a los avances tecnológicos actuales como la construcción de enormes telescopios o satélites con instrumentos cada vez más potentes, hemos avanzado mucho en el estudio del universo que nos rodea. Sin embargo, resulta inquietante que la mayor parte de los componentes del universo (tanto en materia como en energía), aún nos son desconocidos. En la "receta" para "armar" un universo como el nuestro, tenemos que poner dos ingredientes que son, hasta el momento, un gran enigma. En principio, debemos contar la llamada "energía oscura", que produce la expansión acelerada a gran escala de todo el universo. Se estima que equivale al 70% de la densidad de energía total del universo... pero aún no podemos explicar su verdadera naturaleza.

¿Qué queda del resto del universo? El resto es materia, podemos pensar aliviados. Sin embargo, la materia que conocemos, la que forma las galaxias, sus estrellas, nebulosas, planetas y toda la lista de magníficos astros, representa apenas un 4% del presupuesto total de densidad de energía del universo (recordemos que la energía y la materia son equivalentes). El resto de la receta, ese 26% faltante, constituye otro enorme misterio: "la materia oscura".

En una bizarra comparación con los humanos, podríamos decir que la materia "normal" es materia "extrovertida". Se manifiesta de innumerables maneras: la podemos detectar porque emite luz (por ejemplo, en las estrellas) o la refleja (como los planetas), ejerce fuerza de gravedad armando estrellas, sistemas estelares o uniendo las componentes de las galaxias, se relaciona con otra materia "normal" mediante fuerzas magnéticas o eléctricas. Es decir, se la puede detectar directamente con telescopios e instrumentos adecuados. Además, es la materia que nos compone, razón por la cual la podemos estudiar y conocer con gran profundidad.

Sin embargo, la mayor parte de la materia del universo, la materia oscura, es... "introvertida". Esa materia quizás esté en todas partes, aún frente a nuestros mejores detectores, pero no la podemos ver. Tímidamente, sólo se da a conocer mediante la fuerza gravitatoria. No brilla y no interactúa mediante otras fuerzas de la naturaleza, excepto por medio de la gravitación. Y como excede enormemente en cantidad a la materia normal, condiciona muchas propiedades de las galaxias tales como su forma, sus movimientos, sus vínculos con otras galaxias y la distribución de la materia en sus interiores.

Enmarcado en los arduos esfuerzos para comprender la naturaleza de la materia oscura y su influencia sobre las galaxias, el Dr. Carlos R. Argüelles, investigador del IALP (CONICET-UNLP), ICRANet y docente de la Facultad de Ciencias Exactas de la UNLP, junto a un equipo de investigadores de Italia y Francia, ha realizado un artículo que sale publicado hoy, primero de marzo de 2023, que arroja nueva luz sobre el tema, en la prestigiosa revista científica The Astrophysical Journal.

Este grupo de astrónomos ha construido un modelo teórico para la distribución de la materia oscura en las galaxias, el cual predice la formación de regiones extendidas llamadas "halos". Ellos consideran que la materia oscura está compuesta por algún tipo de partícula subatómica de la clase de los "fermiones". Los fermiones constituyen un extenso grupo de partículas que engloba, por sus propiedades cuánticas, por ejemplo, a los electrones, protones o neutrones. Se los diferencia de los "bosones" por una característica cuántica llamada espín, que hace que su comportamiento sea diferente. Entre los bosones la partícula más conocida es el fotón (la partícula de luz). Los autores del modelo sólo asumen que los fermiones de materia oscura deben ser livianos (menos masivos que un electrón), ser neutros (sin carga eléctrica) y que no sienten ninguna fuerza salvo la gravedad. Así, ellos construyen su modelo usando propiedades generales de los fermiones y la gravedad, basándose directamente en la física conocida. De este modo, los investigadores muestran que el modelo de halo de materia oscura fermiónica es capaz de explicar, simultáneamente, muchas de las propiedades observadas en la materia normal (la cual no es suficiente para dar cuenta de las mismas), tales como su distribución y sus movimientos en diferentes clases de galaxias.

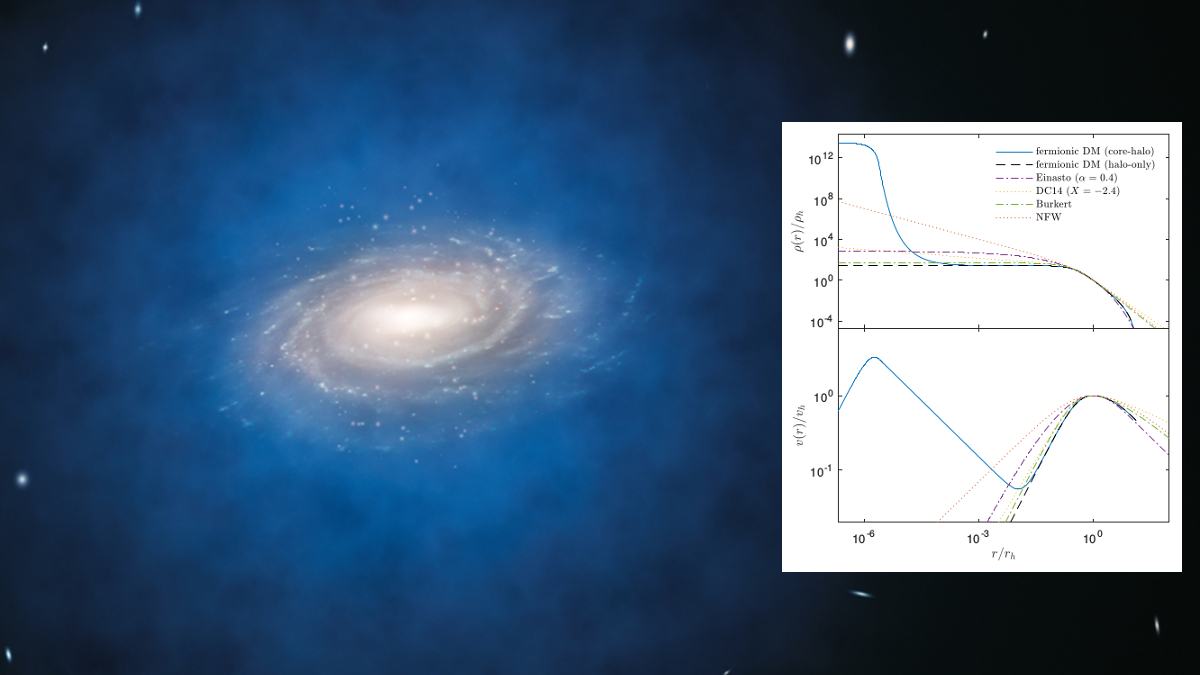

Uno de los resultados más importantes del trabajo se refiere a la rotación de aquellas galaxias cuya materia se distribuye en forma de un disco chato (un disco en rotación, compuesto por miles de millones de estrellas y nebulosas de gas y polvo, como se ve en la figura). En esos casos, el modelo puede dar cuenta de cómo rotan las estrellas pertenecientes a estos discos galácticos bajo la influencia del halo de materia oscura, detallando sus velocidades desde sus regiones más internas hasta los bordes exteriores. Los astrónomos usan un gráfico de la velocidad de rotación con respecto a la distancia al centro de la galaxia: una "curva de rotación galáctica" (ver figura inserta). Por ejemplo, si las estrellas y componentes de la región central de una galaxia rotan más rápidamente que las estrellas de los bordes de la galaxia, la curva de rotación tendrá una forma decreciente. Justamente, la materia oscura se descubrió (allá por los años '60 y '70) porque las curvas de rotación tenían una forma peculiar. Eran aproximadamente planas en sus regiones externas, lo que requería de la existencia de mucha más materia que la observada.

Volviendo al artículo, los autores usaron las curvas de rotación de 120 galaxias observadas de la base de datos SPARC (Spitzer Photometry & Accurate Rotation Curves), obtenida mediante el telescopio espacial Spitzer. Con esta enorme cantidad de datos, pudieron distinguir la contribución a la rotación galáctica atribuible a la materia normal de aquella atribuible a la materia oscura, de manera de poder testear el modelo. Luego compararon las predicciones de este con los resultados de otros modelos publicados previamente que usan diferentes hipótesis sobre la distribución de materia oscura, mostrando las diferencias y ventajas del modelo propio.

Una de las predicciones más importantes que obtienen es, precisamente, la distribución de materia oscura desde el centro galáctico hacia su periferia. El modelo de halo fermiónico predice una distribución esférica de materia oscura heterogénea, la cual se encuentra altamente concentrada hacia el centro, siendo mas diluida hacia la región externa ocupada por el disco. Este resultado está en concordancia con las observaciones de curvas de rotación galactica (cuyos datos sólo son accesibles en las partes externas), mientras que arroja una novedosa predicción respecto de su distribución en la parte mas central. Esta última no puede ser reproducida por otros modelos de materia oscura basados en simulaciones numéricas de muchos cuerpos puntuales de masa, las cuales se utilizan en la actualidad (ver la figura inserta).

El modelo de halo de materia oscura fermiónica representa un potencial avance en la interpretación de muchas propiedades observadas en las galaxias, las cuales hasta el momento, sólo han sido explicadas mediante modelos fenomenológicos basados en simulaciones numéricas. En cambio, este es un modelo unificador, basado en las propiedades físicas básicas de los fermiones y la gravedad, en su capacidad de contribuir, como materia oscura, a la estructura y dinámica interna de las galaxias. De este modo, el trabajo de Argüelles y sus colaboradores nos acerca un paso más a la ansiada meta de develar el insondable misterio de la naturaleza de la materia oscura.

Título del artículo: "Galaxy rotation curves and universal scaling relations: comparison between phenomenological and fermionic dark matter profiles"

Autores: A. Krut (Italia), C. R. Argüelles (IALP, UNLP-CONICET, ICRANet), P. H. Chavanis (Francia), J. A. Rueda (Italia) y R. Ruffini (Italia).

Enlace al artículo preliminar: https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.02020

Redacción de la nota: Dr. Roberto O. J. Venero (IALP, FCAG, UNLP).

English version

Title: Dark matter halos: the key to understanding galaxies

We have come a long way in understanding the universe around us, thanks to current technological advances, such as the construction of huge telescopes or satellites with increasingly powerful instruments. However, it is disturbing that most of the universe components (matter and energy) are still unknown to us. In the "recipe" to "build" a universe like ours, we have to put two ingredients that are, up to now, a great enigma. In principle, we must count the so-called "dark energy" which produces the large-scale accelerated expansion of the entire universe. It is estimated to be equivalent to 70% of the total energy density of the universe, but we still cannot explain its true nature.

What is left of the rest of the universe? The rest is matter we can think with relief. However, the matter that we know, which forms galaxies, their stars, nebulae, planets and the entire list of magnificent celestial objects, represents barely 4% of the total energy density balance of the universe (remember that energy and matter are equivalent ). The rest of the recipe, that remaining 26%, constitutes another great mystery: "dark matter."

In a bizarre comparison to humans, "normal" matter would be "extroverted" matter. It manifests itself in countless ways: we can detect it because it emits light (for example, in stars) or reflects it (like planets), it exerts the force of gravity by assembling stars, stellar systems, or the components of galaxies, it interacts with other "normal" matter by magnetic or electrical forces. That is, it can be detected directly with appropriate telescopes and instruments. In addition, it is a matter that makes us up, so we can study it and know it in depth.

However, most of the matter in the universe, dark matter, is... "introverted." That stuff can be everywhere, even in front of our best detectors, but we can't see it. Timidly, it only makes itself known through the gravitational force. It does not shine or interact with other forces of nature except through gravitation. And since it vastly exceeds ordinary matter in quantity, it conditions many properties of galaxies, such as their shape, kinematics, connection with other galaxies, and the distribution of matter within them.

Framed in the arduous efforts to understand the nature of dark matter and its influence on galaxies, Dr. Carlos R. Argüelles, IALP (CONICET-UNLP) researcher and professor at the UNLP Faculty of Exact Sciences & ICRANet, together with a team of researchers from Italy and France, has published today, March 1, 2023, an article that sheds new light on the subject, in the prestigious scientific journal The Astrophysical Journal.

This group of astronomers has built a theoretical model for the distribution of dark matter in galaxies, which predicts the formation of large regions called "halos." They propose that dark matter is a subatomic particle of the "fermion" class. Fermions constitute an extensive group of particles that encompasses, due to their quantum properties, for example, electrons, protons, and neutrons. Fermions differ from "bosons" by spin, a quantum property that makes their behavior different. Among the bosons, the best-known particle is the photon (the particle of light). The proposed model considers only that dark matter fermions must be light (less massive than an electron), neutral (no electrical charge), and experience no force except gravity. Therefore, the researchers build their model using the general properties of fermions and gravity, drawing directly from known physical principles. In this way, the researchers demonstrate that the fermionic dark matter halo model can simultaneously explain many of the properties observed in ordinary matter (which is not enough to account for them), such as its distribution and their inner kinematics in different classes of galaxies.

One of the most important results of the work refers to the rotation of those galaxies whose matter is distributed in the form of a flat disk (a rotating disk made up of billions of stars and nebulae of gas and dust, as seen in the figure). In those cases, the model can account for the way in which the stars belonging to these galactic disks rotate under the influence of the dark matter halo, detailing their speeds from their innermost regions to their outer edges. Astronomers use a graph of the rate of rotation velocity versus distance from the center of the galaxy: a "galactic rotation curve" (see inset figure below). For example, if the stars and components in the central region of a galaxy rotate faster than the stars at the edges of the galaxy, the rotation curve will have a decreasing slope. Dark matter was discovered precisely (back in the '60s and '70s) because the rotation curves had a peculiar shape. They were roughly flat in their outer regions, which required the existence of much more matter than observed.

The paper's authors used the observational rotation curves of 120 galaxies from the SPARC (Spitzer Photometry & Accurate Rotation Curves) database obtained with the Spitzer Space Telescope. With this huge amount of data, they distinguished the contribution to galactic rotation attributable to ordinary matter from that corresponding to dark matter, allowing to test the model. Next, they compared the predictions of this with the results of other previously published models that use different hypotheses about the distribution of dark matter, showing the differences and advantages of the proposed model.

One of the most relevant predictions they obtain is the distribution of dark matter from the galactic center to the outer edge. The fermionic halo model predicts a spherical distribution of heterogeneous dark matter, which is highly concentrated towards the center, being more dilute towards the outer region occupied by the disk. This result agrees with the observations of galactic rotation curves (for which data are only accessible in the outer parts) but include a novel prediction regarding its distribution in the most central region. This overall distribution of matter cannot be reproduced by other dark matter models based on numerical N-body simulations of current use (see inset figure above).

The fermionic dark matter halo model represents a potential advance in the interpretation of many observed properties of galaxies. Until now, these properties were explained by phenomenological models based on numerical simulations. Instead, this is a unifying model, based on the basic physical properties of fermions and gravity, on their ability to contribute, as dark matter, to the internal structure and dynamics of galaxies. In this way, the work of Argüelles and his collaborators brings us one step closer to the long-awaited goal of unveiling the unfathomable mystery of the nature of dark matter.

Article title: "Galaxy rotation curves and universal scaling relations: comparison between phenomenological and fermionic dark matter profiles"

Authors: A. Krut (Italy), C. R. Argüelles (IALP, UNLP-CONICET, ICRANet), P. H. Chavanis (France), J. A. Rueda (Italy) and R. Ruffini (Italy).

Link to preliminary article: https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.02020

Note by Dr. Roberto O. J. Venero (IALP, FCAG, UNLP).

Photo: In the background image, an artist's representation of a disk galaxy, which appears immersed in a halo of invisible dark matter, represented as a diffuse blue cloud (Credits:ESO/L. Calçada). Inserted in the graph, you can see the comparison of the dark matter distribution (density) for a typical spiral galaxy predicted by the fermionic halo model (solid blue line) compared to other models (cited in the original work). It is clear that the model of Argüelles and his collaborators predicts a novel distribution for dark matter, which is similar to that offered by other models in its external part, but which acquires a high concentration towards its interior. This distribution could have profound implications for the nature of supermassive black holes (most galaxies are assumed to have a supermassive black hole at their centers). Below, the corresponding rotation speed curve is plotted, compared with other models (graphs taken from the scientific article).